Introductory Networking

An introduction to networking theory and basic networking tools

💢 We will cover the topics

- Network Fundamentals

- Network Forensics

- Network Enumaration

Task 1 Introduction

The aim of this room is to provide a beginner's introduction to the basic principles of networking. Networking is a massive topic, so this really will just be a brief overview; however, it will hopefully give you some foundational knowledge of the topic, which you can build upon for yourself.

The topics that we're going to cover in this room are:

- The OSI Model

- The TCP/IP Model

- How these models look in practice

- An introduction to basic networking tools

- Let's get started!

No answer needed

Task 2 The OSI Model: An Overview

The OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) Model is a standardised model which we use to demonstrate the theory behind computer networking. In practice, it's actually the more compact TCP/IP model that real-world networking is based off; however the OSI model, in many ways, is easier to get an initial understanding from.

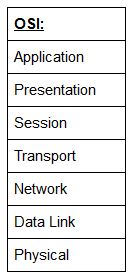

The OSI model consists of seven layers:

There are many mnemonics floating around to help you learn the layers of the OSI model -- search around until you find one that you like.

I personally favour: Anxious Pale Shakespeare Treated Nervous Drunks Patiently

Let's briefly take a look at each of these in turn:

Layer 7 -- Application:

The application layer of the OSI model essentially provides networking options to programs running on a computer. It works almost exclusively with applications, providing an interface for them to use in order to transmit data. When data is given to the application layer, it is passed down into the presentation layer.

Layer 6 -- Presentation:

The presentation layer receives data from the application layer. This data tends to be in a format that the application understands, but it's not necessarily in a standardised format that could be understood by the application layer in the receiving computer. The presentation layer translates the data into a standardised format, as well as handling any encryption, compression or other transformations to the data. With this complete, the data is passed down to the session layer.

Layer 5 -- Session:

When the session layer receives the correctly formatted data from the presentation layer, it looks to see if it can set up a connection with the other computer across the network. If it can't then it sends back an error and the process goes no further. If a session can be established then it's the job of the session layer to maintain it, as well as co-operate with the session layer of the remote computer in order to synchronise communications. The session layer is particularly important as the session that it creates is unique to the communication in question. This is what allows you to make multiple requests to different endpoints simultaneously without all the data getting mixed up (think about opening two tabs in a web browser at the same time)! When the session layer has successfully logged a connection between the host and remote computer the data is passed down to Layer 4: the transport Layer.

Layer 4 -- Transport:

The transport layer is a very interesting layer that serves numerous important functions. Its first purpose is to choose the protocol over which the data is to be transmitted. The two most common protocols in the transport layer are TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol); with TCP the transmission is connection-based which means that a connection between the computers is established and maintained for the duration of the request. This allows for a reliable transmission, as the connection can be used to ensure that the packets all get to the right place. A TCP connection allows the two computers to remain in constant communication to ensure that the data is sent at an acceptable speed, and that any lost data is re-sent. With UDP, the opposite is true; packets of data are essentially thrown at the receiving computer -- if it can't keep up then that's its problem (this is why a video transmission over something like Skype can be pixelated if the connection is bad). What this means is that TCP would usually be chosen for situations where accuracy is favoured over speed (e.g. file transfer, or loading a webpage), and UDP would be used in situations where speed is more important (e.g. video streaming).

With a protocol selected, the transport layer then divides the transmission up into bite-sized pieces (over TCP these are called segments, over UDP they're called datagrams), which makes it easier to transmit the message successfully.

Layer 3 -- Network:

The network layer is responsible for locating the destination of your request. For example, the Internet is a huge network; when you want to request information from a webpage, it's the network layer that takes the IP address for the page and figures out the best route to take. At this stage we're working with what is referred to as Logical addressing (i.e. IP addresses) which are still software controlled. Logical addresses are used to provide order to networks, categorising them and allowing us to properly sort them. Currently the most common form of logical addressing is the IPV4 format, which you'll likely already be familiar with (i.e 192.168.1.1 is a common address for a home router).

Layer 2 -- Data Link:

The data link layer focuses on the physical addressing of the transmission. It receives a packet from the network layer (that includes the IP address for the remote computer) and adds in the physical (MAC) address of the receiving endpoint. Inside every network enabled computer is a Network Interface Card (NIC) which comes with a unique MAC (Media Access Control) address to identify it.

MAC addresses are set by the manufacturer and literally burnt into the card; they can't be changed -- although they can be spoofed. When information is sent across a network, it's actually the physical address that is used to identify where exactly to send the information.

Additionally, it's also the job of the data link layer to present the data in a format suitable for transmission.

The data link layer also serves an important function when it receives data, as it checks the received information to make sure that it hasn't been corrupted during transmission, which could well happen when the data is transmitted by layer 1: the physical layer.

Layer 1 -- Physical:

The physical layer is right down to the hardware of the computer. This is where the electrical pulses that make up data transfer over a network are sent and received. It's the job of the physical layer to convert the binary data of the transmission into signals and transmit them across the network, as well as receiving incoming signals and converting them back into binary data.

For the "Which Layer" Questions below, answer using the layer number (1-7)

- Which layer would choose to send data over TCP or UDP?

4

- Which layer checks received packets to make sure that they haven't been corrupted?

2

- In which layer would data be formatted in preparation for transmission?

2

- Which layer transmits and receives data?

1

- Which layer encrypts, compresses, or otherwise transforms the initial data to give it a standardised format?

6

- Which layer tracks communications between the host and receiving computers?

5

- Which layer accepts communication requests from applications?

7

- Which layer handles logical addressing?

3

- When sending data over TCP, what would you call the "bite-sized" pieces of data?

segments

- [Research] Which layer would the FTP protocol communicate with?

7

- Which transport layer protocol would be best suited to transmit a live video?

udp

Task 3 Encapsulation

As the data is passed down each layer of the model, more information containing details specific to the layer in question is added on to the start of the transmission. As an example, the header added by the Network Layer would include things like the source and destination IP addresses, and the header added by the Transport Layer would include (amongst other things) information specific to the protocol being used. The data link layer also adds a piece on at the end of the transmission, which is used to verify that the data has not been corrupted on transmission; this also has the added bonus of increased security, as the data can't be intercepted and tampered with without breaking the trailer. This whole process is referred to as encapsulation; the process by which data can be sent from one computer to another.

Notice that the encapsulated data is given a different name at different steps of the process. In layers 7,6 and 5, the data is simply referred to as data. In the transport layer the encapsulated data is referred to as a segment or a datagram (depending on whether TCP or UDP has been selected as a transmission protocol). At the Network Layer, the data is referred to as a packet. When the packet gets passed down to the Data Link layer it becomes a frame, and by the time it's transmitted across a network the frame has been broken down into bits.

When the message is received by the second computer, it reverses the process -- starting at the physical layer and working up until it reaches the application layer, stripping off the added information as it goes. This is referred to as de-encapsulation. As such you can think of the layers of the OSI model as existing inside every computer with network capabilities. Whilst it's not actually as clear cut in practice, computers all follow the same process of encapsulation to send data and de-encapsulation upon receiving it.

The processes of encapsulation and de-encapsulation are very important -- not least because of their practical use, but also because they give us a standardised method for sending data. This means that all transmissions will consistently follow the same methodology, allowing any network enabled device to send a request to any other reachable device and be sure that it will be understood -- regardless of whether they are from the same manufacturer; use the same operating system; or any other factors.

- How would you refer to data at layer 2 of the encapsulation process (with the OSI model)?

Frames

- How would you refer to data at layer 4 of the encapsulation process (with the OSI model), if the UDP protocol has been selected?

Datagrams

- What process would a computer perform on a received message?

de-encapsulation

- Which is the only layer of the OSI model to add a trailer during encapsulation?

Data Link

- Does encapsulation provide an extra layer of security (Aye/Nay)?

Aye

Task 4 The TCP/IP Model

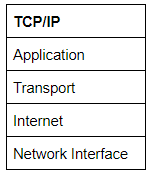

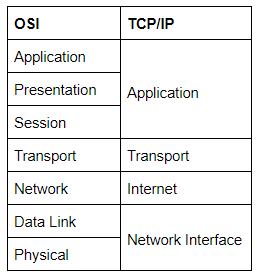

The TCP/IP model is, in many ways, very similar to the OSI model. It's a few years older, and serves as the basis for real-world networking. The TCP/IP model consists of four layers: Application, Transport, Internet and Network Interface. Between them, these cover the same range of functions as the seven layers of the OSI Model.

You would be justified in asking why we bother with the OSI model if it's not actually used for anything in the real-world. The answer to that question is quite simply that the OSI model (due to being less condensed and more rigid than the TCP/IP model) tends to be easier for learning the initial theory of networking.

The two models match up something like this:

The processes of encapsulation and de-encapsulation work in exactly the same way with the TCP/IP model as they do with the OSI model. At each layer of the TCP/IP model a header is added during encapsulation, and removed during de-encapsulation.

Now let's get down to the practical side of things.

A layered model is great as a visual aid -- it shows us the general process of how data can be encapsulated and sent across a network, but how does it actually happen?

When we talk about TCP/IP, it's all well and good to think about a table with four layers in it, but we're actually talking about a suite of protocols -- sets of rules that define how an action is to be carried out. TCP/IP takes its name from the two most important of these: the Transmission Control Protocol (which we touched upon earlier in the OSI model) that controls the flow of data between two endpoints, and the Internet Protocol, which controls how packets are addressed and sent. There are many more protocols that make up the TCP/IP suite; we will cover some of these in later tasks. For now though, let's talk about TCP.

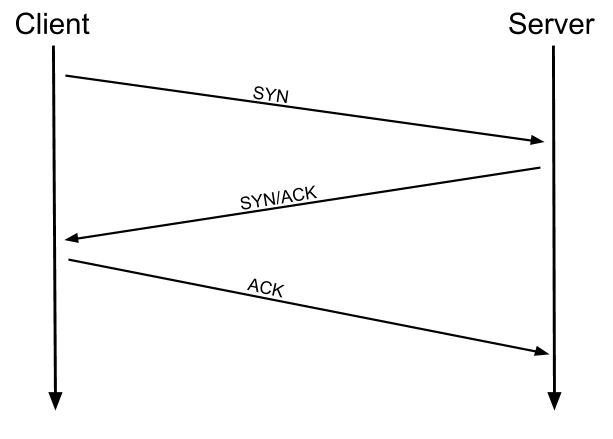

As mentioned earlier, TCP is a connection-based protocol. In other words, before you send any data via TCP, you must first form a stable connection between the two computers. The process of forming this connection is called the three-way handshake.

When you attempt to make a connection, your computer first sends a special request to the remote server indicating that it wants to initialise a connection. This request contains something called a SYN (short for synchronise) bit, which essentially makes first contact in starting the connection process. The server will then respond with a packet containing the SYN bit, as well as another "acknowledgement" bit, called ACK. Finally, your computer will send a packet that contains the ACK bit by itself, confirming that the connection has been setup successfully. With the three-way handshake successfully completed, data can be reliably transmitted between the two computers. Any data that is lost or corrupted on transmission is re-sent, thus leading to a connection which appears to be lossless.

(Credit Kieran Smith, Abertay University)

We're not going to go into exactly how this works on a step-to-step level -- not in this room at any rate. It is sufficient to know that the three-way handshake must be carried out before a connection can be established using TCP.

History:

It's important to understand exactly why the TCP/IP and OSI models were originally created. To begin with there was no standardisation -- different manufacturers followed their own methodologies, and consequently systems made by different manufacturers were completely incompatible when it came to networking. The TCP/IP model was introduced by the American DoD in 1982 to provide a standard -- something for all of the different manufacturers to follow. This sorted out the inconsistency problems. Later the OSI model was also introduced by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO); however, it's mainly used as a more comprehensive guide for learning, as the TCP/IP model is still the standard upon which modern networking is based.

- Which model was introduced first, OSI or TCP/IP?

TCP/IP

- Which layer of the TCP/IP model covers the functionality of the Transport layer of the OSI model (Full Name)?

Transport

- Which layer of the TCP/IP model covers the functionality of the Session layer of the OSI model (Full Name)?

Application

- The Network Interface layer of the TCP/IP model covers the functionality of two layers in the OSI model. These layers are Data Link, and?.. (Full Name)?

Physical

- Which layer of the TCP/IP model handles the functionality of the OSI network layer?

Internet

- What kind of protocol is TCP?

connection-based

- What is SYN short for?

synchronise

- What is the second step of the three way handshake?

SYN/ACK

- What is the short name for the "Acknowledgement" segment in the three-way handshake?

ACK

Task 5 Wireshark

We've gone over the basic theory -- now let's put it into practice! In this task we're going to look at some captured network traffic to see the advantages of understanding the OSI and TCP/IP Models.

Wireshark is a tool used to capture and analyse packets of data going across a network.

We're going to use Wireshark to get an idea of what these models look like in practice, with real world data.

Download the attached .pcap file (Wireshark capture) and follow along!

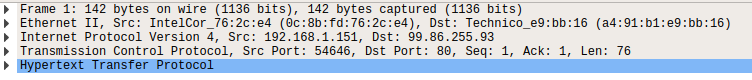

When you first load the packet into Wireshark you're given a list of captured data in the top window (there are two items in this window just now), and in the bottom two windows you're shown the data contained in each captured packet of data:

Currently we're looking at the first packet, so let's have a look at the data in a little more detail:

There are 5 pieces of information here:

- Frame 1 -- this is showing details from the physical layer of the OSI model (Network Interface layer of the TCP/IP model): the size of the packet received in terms of bytes)

- Ethernet II -- this is showing details from the Data Link layer of the OSI model (Network Interface layer of the TCP/IP model): the transmission medium (in this case an Ethernet cable), as well as the source and destination MAC addresses of the request.

- Internet Protocol Version 4 -- this is showing details from the Network layer of the OSI model (Internet Layer of the TCP/IP model): the source and destination IP addresses of the request.

- Transmission Control Protocol -- this is showing details from the Transport layer of the OSI and TCP/IP models: in this case it's telling us that the protocol was TCP, along with a few other things that we're not covering here.

- Hypertext Transfer Protocol -- this is showing details from the Application layer of the OSI and TCP/IP models: specifically, this is a HTTP GET request, which is requesting a web page from a remote server.

This is not a Wireshark room, so we're not going to go into any more depth than that. The important thing is that you understand how the theory you learnt earlier translated into a real life scenario.

With that in mind, click on the second captured packet (in the top window) and answer the following questions:

- What is the protocol specified in the section of the request that's linked to the Application layer of the OSI and TCP/IP Models?

Domain Name System

- Which layer of the OSI model does the section that shows the IP address "172.16.16.77" link to (Name of the layer)?

Network

- In the section of the request that links to the Transport layer of the OSI and TCP/IP models, which protocol is specified?

User Datagram Protocol

- Over what medium has this request been made (linked to the Data Link layer of the OSI model)?

Ethernet II

- Which layer of the OSI model does the section that shows the number of bytes transferred (81) link to?

Physical

- [Research] Can you figure out what kind of address is shown in the layer linked to the Data Link layer of the OSI model?

MAC

Task 6 [Networking Tools] Ping

At this stage, hopefully all of the theory has made sense and you now understand the basic models behind computer networking. For the rest of the room we're going to be taking a look at some of the command line networking tools that we can use in practical applications. Many of these tools do work on other operating systems, but for the sake of simplicity, I'm going to assume that you're running Linux for the rest of this room. The first tool that we're going to look at will be the ping command.

The ping command is used when we want to test whether a connection to a remote resource is possible. Usually this will be a website on the internet, but it could also be for a computer on your home network if you want to check if it's configured correctly. Ping works using the ICMP protocol, which is one of the slightly less well-known TCP/IP protocols that I mentioned earlier. The ICMP protocol works on the Network layer of the OSI Model, and thus the Internet layer of the TCP/IP model. The basic syntax for ping is ping <target>. In this example I am using ping to test whether a network connection to Google is possible:

Notice that the ping command actually returned the IP address for the Google server that it connected to, rather than the URL that I requested. This is a handy secondary application for ping, as it can be used to determine the IP address of the server hosting a website. One of the big advantages of ping is that it's pretty much ubiquitous to any network enabled device. All operating systems support it out of the box, and even most embedded devices can use ping!

Have a go at the following questions. Any questions about syntax can be answered using the man page for ping (man ping on Linux).

- What command would you use to ping the bbc.co.uk website?

ping bbc.co.uk

- Ping muirlandoracle.co.uk What is the IP address?

217.160.0.152

- What switch lets you change the interval of sent ping requests?

-i

- What switch would allow you to restrict requests to IPV4?

-4

- What switch would give you a more verbose output?

-v

Task 7 [Networking Tools] Traceroute

The logical follow-up to the ping command is 'traceroute'. The easiest way to understand what traceroute does is to think of your home network. Say, for example, that you have a wireless router. Your phone is connected to it, as is your computer. What happens if you want to send something to your phone from your computer? You can't just send stuff directly to your phone -- not without directly connecting them, so how would the information get across? The request would first be sent to your router which acts as a gateway. The router knows every device that's connected to it, ergo, it knows how to get to your phone. The router then forwards your request on to your phone and facilitates the return connection in the same way. Traceroute can be used to map the path your request takes as it heads to the target machine.

The internet is made up of many, many different servers and end-points, all networked up to each other. This means that, in order to get to the content you actually want, you first need to go through a bunch of other servers. Traceroute allows you to see each of these connections -- it allows you to see every intermediate step between your computer and the resource that you requested. The basic syntax for traceroute on Linux is this: traceroute <destination>

By default, traceroute operates using the same ICMP protocol that ping utilises, however, this can be altered with switches.

You can see that it took 13 hops to get from my router (_gateway) to the Google server at 216.58.205.46

Now it's your turn. As with before, all questions about switches can be answered with the man page for traceroute (man traceroute).

- Use traceroute on tryhackme.com Can you see the path your request has taken?

No answer needed

- What switch would you use to specify an interface when using Traceroute?

-i

- What switch would you use if you wanted to use TCP requests when tracing the route?

-t

- [Lateral Thinking] Which layer of the TCP/IP model will traceroute run on by default?

Internet

Task 8 [Networking Tools] WHOIS

Domain Names -- the unsung saviours of the internet.

Can you imagine how it would feel to remember the IP address of every website you want to visit? Horrible thought.

Fortunately, we've got domains.

We'll talk a little bit more about how this works in the next task, but for now suffice to know that a domain translates into an IP address so that we don't need to remember it (e.g. you can type tryhackme.com, rather than the TryHackMe IP address). Domains are leased out by companies called Domain Registrars. If you want a domain, you go and register with a registrar, then lease the domain for a certain length of time.

Enter Whois.

Whois essentially allows you to query who a domain name is registered to. In Europe personal details are redacted; however, elsewhere you can potentially get a great deal of information from a whois search.

There is a web version of the whois tool if you're particularly adverse to the command line. Either way, let's get started!

(Note: You may need to install whois before using it. On Debian based systems this can be done with sudo apt update && sudo apt-get install whois)

Whois lookups are very easy to perform. Just use whois <domain> to get a list of available information about the domain registration:

This is comparatively a very small amount of information as can often be found. Notice that we've got the domain name, the company that registered the domain, the last renewal, and when it's next due, and a bunch of information about nameservers (which we'll look at in the next task).

Your Turn

- Perform a whois search on facebook.com

No answer needed

- What is the registrant postal code for facebook.com?

94025

- When was the facebook.com domain first registered?

29/03/1997

- Perform a whois search on microsoft.com

No answer needed

- Which city is the registrant based in?

Redmond

- [OSINT] What is the name of the golf course that is near the registrant address for microsoft.com?

Bellevue Golf Course

- What is the registered Tech Email for microsoft.com?

msnhst@microsoft.com

Task 9 [Networking Tools] Dig

We talked about domains in the previous task -- now lets talk about how they work.

Ever wondered how a URL gets converted into an IP address that your computer can understand? The answer is a TCP/IP protocol called DNS (Domain Name System).

At the most basic level, DNS allows us to ask a special server to give us the IP address of the website we're trying to access. For example, if we made a request to www.google.com, our computer would first send a request to a special DNS server (which your computer already knows how to find). The server would then go looking for the IP address for Google and send it back to us. Our computer could then send the request to the IP of the Google server.

Let's break this down a bit.

You make a request to a website. The first thing that your computer does is check its local cache to see if it's already got an IP address stored for the website; if it does, great. If not, it goes to the next stage of the process.

Assuming the address hasn't already been found, your computer will then send a request to what's known as a recursive DNS server. These will automatically be known to the router on your network. Many Internet Service Providers (ISPs) maintain their own recursive servers, but companies such as Google and OpenDNS also control recursive servers. This is how your computer automatically knows where to send the request for information: details for a recursive DNS server are stored in your router. This server will also maintain a cache of results for popular domains; however, if the website you've requested isn't stored in the cache, the recursive server will pass the request on to a root name server.

There are precisely 13 root name DNS servers in the world. The root name servers essentially keep track of the DNS servers in the next level down, choosing an appropriate one to redirect your request to. These lower level servers are called Top-Level Domain servers.

Top-Level Domain (TLD) servers are split up into extensions. So, for example, if you were searching for tryhackme.com your request would be redirected to a TLD server that handled .com domains. If you were searching for bbc.co.uk your request would be redirected to a TLD server that handles .co.uk domains. As with root name servers, TLD servers keep track of the next level down: Authoritative name servers. When a TLD server receives your request for information, the server passes it down to an appropriate Authoritative name server.

Authoritative name servers are used to store DNS records for domains directly. In other words, every domain in the world will have its DNS records stored on an Authoritative name server somewhere or another; they are the source of the information. When your request reaches the authoritative name server for the domain you're querying, it will send the relevant information back to you, allowing your computer to connect to the IP address behind the domain you requested.

When you visit a website in your web browser this all happens automatically, but we can also do it manually with a tool called dig . Like ping and traceroute, dig should be installed automatically on Linux systems.

Dig allows us to manually query recursive DNS servers of our choice for information about domains: dig <domain> @<dns-server-ip>

It is a very useful tool for network troubleshooting.

This is a lot of information. We're currently most interested in the ANSWER section for this room; however, taking the time to learn what the rest of this means is a very good idea. In summary, that information is telling us that we sent it one query and successfully (i.e. No Errors) received one full answer -- which, as expected, contains the IP address for the domain name that we queried.

Another interesting piece of information that dig gives us is the TTL (Time To Live) of the queried DNS record. As mentioned previously, when your computer queries a domain name, it stores the results in its local cache. The TTL of the record tells your computer when to stop considering the record as being valid -- i.e. when it should request the data again, rather than relying on the cached copy.

The TTL can be found in the second column of the answer section:

It's important to remember that TTL (in the context of DNS caching) is measured in seconds, so the record in the example will expire in two minutes and thirty-seven seconds.

Have a go at some questions about DNS and dig.

- What is DNS short for?

Domain Name System

- What is the first type of DNS server your computer would query when you search for a domain?

recursive

- What type of DNS server contains records specific to domain extensions (i.e. .com, .co.uk, etc)? Use the long version of the name.

Top-Level Domain

- Where is the very first place your computer would look to find the IP address of a domain?

Local Caches

- [Research] Google runs two public DNS servers. One of them can be queried with the IP 8.8.8.8, what is the IP address of the other one?

8.8.4.4

- If a DNS query has a TTL of 24 hours, what number would the dig query show?

86400

Task 10 Further Reading

That's us completed our whirlwind tour of networking basics. Hopefully you've found it informative!

Networking is one of those things that you just need to learn. We've covered the very basics, but I would strongly suggest that you continue to learn by yourself.

In terms of further information, feel free to reach out in the TryHackMe Discord if you want any help with the contents of this room. Additionally, if you want to expand your knowledge of networking theory, the CISCO Self Study Guide by Steve McQuerry is a great resource to work from. I believe there may be a more up to date version available; however, this edition is cheap, readily available, and most importantly, still very relevant. Whilst it is designed to as a study guide for the CCNA exam, that book serves equally well as a very rounded introduction to networking principles.

- Read the final thoughts

No answer needed